Bitstream

“The first Bitstream players sounded dire”, a senior Marantz engineer once told me. Strictly not for publication you understand, but refreshingly candid all the same. At the time, others couched the phrase in rather more diplomatic language, but it’s worth noting that the company didn’t produce a flagship Bitstream machine until 1994’s CD-15. That’s six years – three generations – after the aforementioned Philips machines came out. Marantz was doing some very listenable budget one-bit players by the early nineties (CD52SE, etc.), but didn’t feel it was good enough for high end until later…

![Marantz CD7]() Marantz CD7

Marantz CD7

Bitstream, lest we forget, was a great answer to the question of how to produce inexpensive digital-to-analogue convertor chips with better linearity than the ladder DACs of the nineteen eighties – such as Philips’ iconic TDA1541. This was a sixteen bit, four-times oversampling design and universally loved for its lively, musical sound. The downside was that it was noisy and when poorly implemented could sound harsh or opaque. It was also more expensive to make than running a single bit register at very high speed – and when you’re making gazilions of the things, there’s a lot of money to be saved – and/or spent elsewhere on the product where it might make more difference.

Marantz CD15

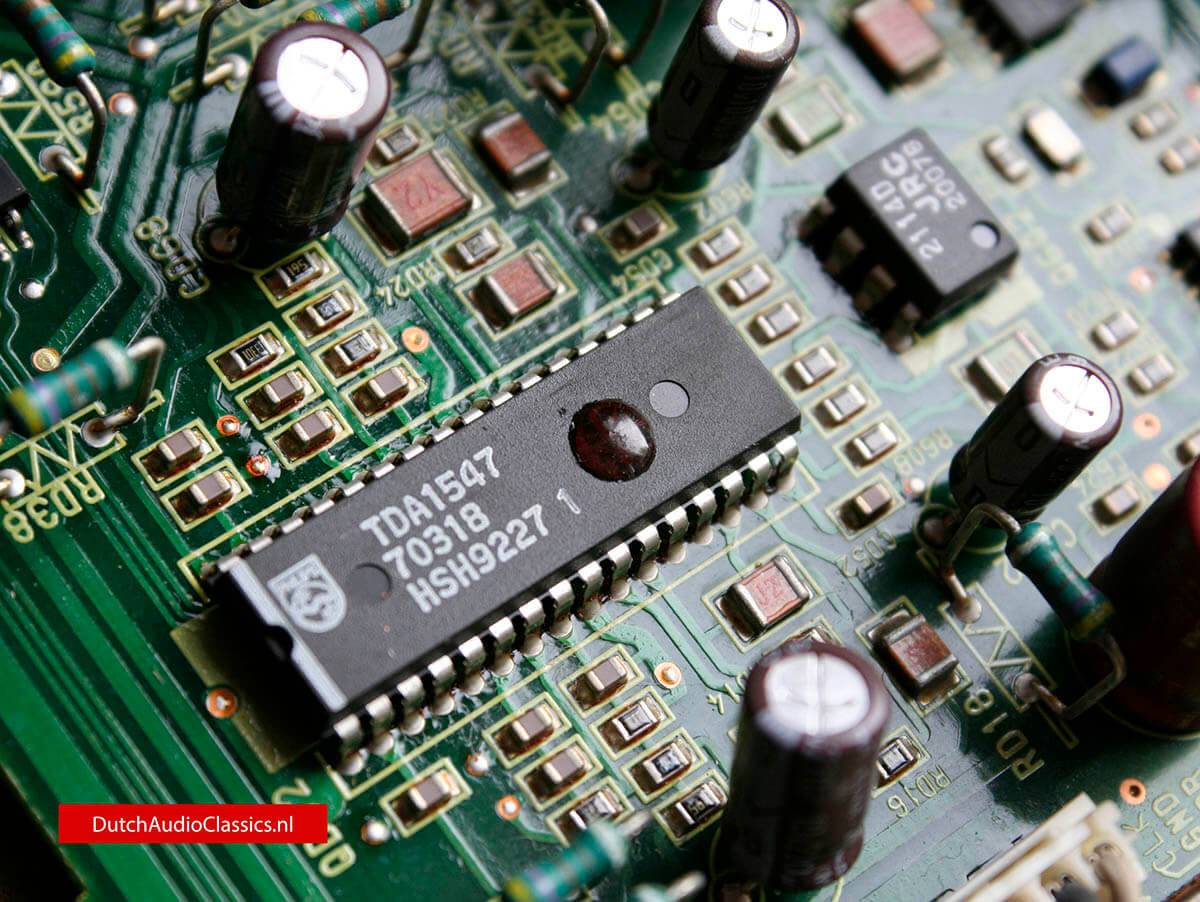

Marantz’s CD-15 was a very good bit of kit, one that was dramatically sonically superior to those first Philips Bitstream designs. Costing £3,000 in the UK and honed by Ken Ishiwata, it sold over five hundred units a year and as you’d expect used an awful lot of Philips bits – including the CDM4 Pro transport mechanism and SAA7350/TDA1547 DACs. A beautiful bit of kit, it looks modern even twenty three years later and set the look for future high end Marantz machines, which haven’t really deviated visually too far ever since. So four years later, when the time came to do a new top end silver disc spinner, you’d expect only some modest changes. Instead however, the company effectively decided to scrap Bitstream and start over!

![Marantz CD15]() Marantz CD15

Marantz CD15

Marantz CD7

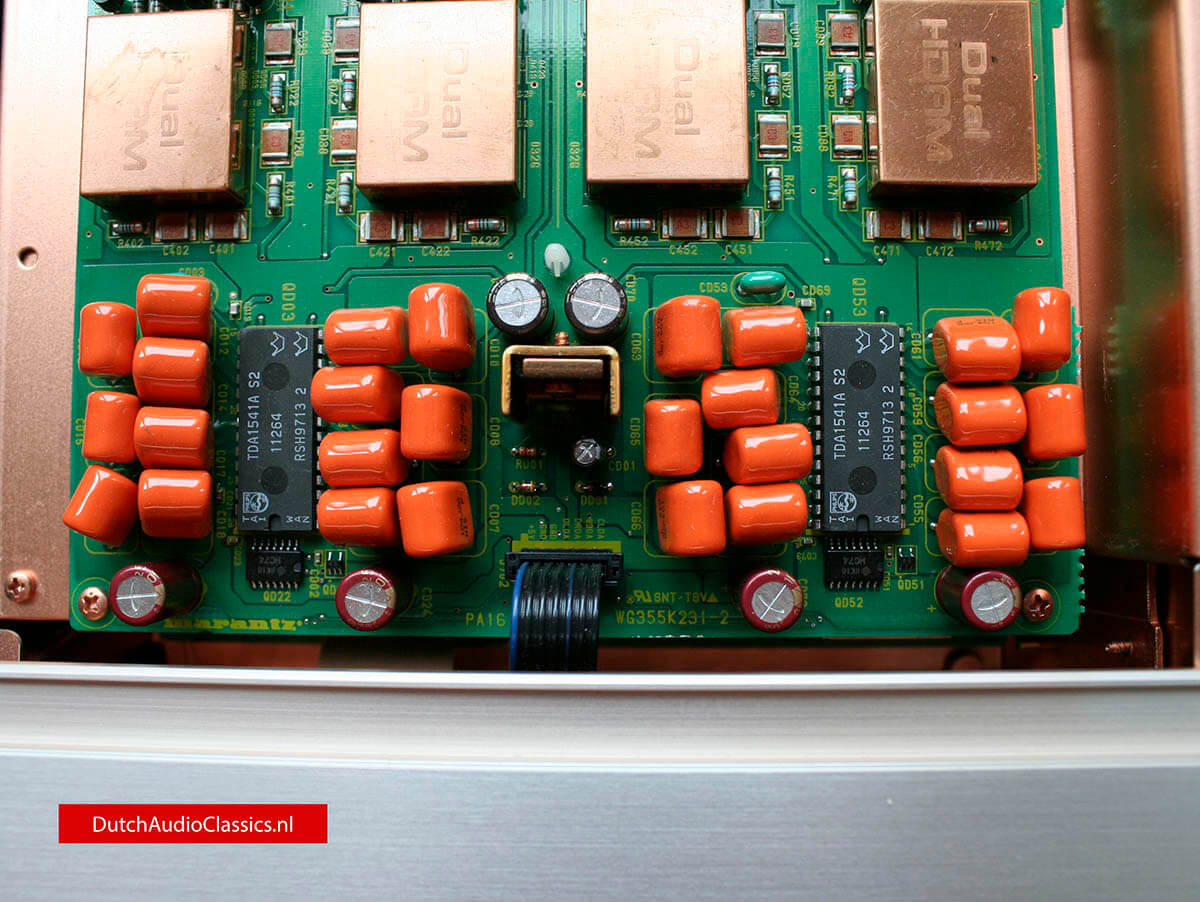

Marantz went back to the pre-Bitstream era with the CD-15’s replacement. It came as something as a shock to many of us, given that we’re always told that new technology is better than the old. The 1998 CD-7 was a tacit acknowledgement that progress is not necessarily a good thing. Although an object of beauty that measured superbly by the standards of the day, its CD-15 predecessor didn’t float many people’s boat. It was thought to sound just a bit too ‘hi-fi’, and believed to lack the organic musical flow of the earlier 16-bit, four times oversampling machines. Knowing that Philips was about to stop making the TDA1541 DAC chips, and that they had already achieved legendary status during their own lifetime, Marantz duly bought the last of the production run and built the CD-7 around them…

This £3,500 CD spinner amazed the world when it came out with an older digital converter than the model it had replaced. Inside was the very best Double Gold Crown version of the TDA1541 running doubled up in differential pairs for maximum linearity. Working in conjunction with these was a new bespoke Linear Music Filter [see box], which effectively comprised of two Motorola 56000 processors running the source code of Philips’ SAA7220 digital filter chips, along with custom Marantz code. Although the player didn’t physically use SAA7220s (which partnered Philips original TDA1541-based players), its DSP chip emulated them to recreate their four times oversampling as well as offering three switchable filtering algorithms, including a special option that vastly improved on the stock filter profiles. The idea was to offer the best versions of the classic DAC chips, with state-of-the-art filtering.

Philips CD Pro (VAU1252) transport

One problem that Marantz had by this time was the lack of a top-flight off-the-shelf transport. You might say that it was the very beginning of the end for CD, as Philips was slowly scaling down and taking the cost out of it. Sadly the superb CDM4 Pro was no more, so Marantz had to make-do-and-mend with the (then) ubiquitous CD12.3. This was duly re-fettled; the metal chassis version was specified and Marantz rebuilt it to their specifications – including diamond milled stainless steel slide bars for super slick disc loading. As with its predecessor, the CD-7 sported a good number of (fourteen, no less) selected Marantz Hyper Dynamic Amplifier Module (HDAMs), and the power supply was breathed on with Shottky diodes, discrete transistor regulation and an ultra low noise ring-core toroidal transformer. Audio-grade selected components were in abundance, while the copper-plated diecast chassis and casing got anti-resonance fixings and vibration damping feet.

![Marantz CD7 and Marantz CD15]() Marantz CD7 and Marantz CD15

Marantz CD7 and Marantz CD15

Custom-designed Linear Music Filter

The digital-to-analogue conversion process produces a huge amount of noise and this has to be filtered out of the audio band. Trouble is, filtering brings its own problems which impact the sound in other ways – the time domain can be and is affected. Filters introduce pre- and post ringing, basically blurring an impulse so that it doesn’t start and stop cleanly, but rather has artefacts before and after the event which in turn smear the sound in the time domain. For the CD-7, Marantz decided to tackle this head on with its own custom-designed Linear Music Filter, which used clever digital signal processing before the digital conversion stage. This acted in a more subtle way, delivering both a flat frequency response and very little phase distortion. It was a development of standard ‘FIR’ digital filter used commonly, but significantly cut down on pre-ringing. Alongside this, a gentle-acting third order Bessel analogue filter offered optimum impulse response and low phase distortion after the digital-to-analogue conversion process. Marantz’s DSP also offered other features such as ‘soft mute’ to eliminate signal noise clicks when activating the stop and pause controls, -12dB track search attention and automatic de-emphasis switching.

Digital inputs

In other respects, the CD-7 was par for the course – for a flagship Marantz silver disc spinner, that is. It sported sonically superior balanced XLR outputs as well as the usual RCA phonos, and a choice of either optical or coaxial digital outs. Alongside those retro DAC chips, the other stand-out feature of this machine was the digital input. It was a highly prescient move, meaning the machine could function as a standalone DAC working at up to 20-bit, 48kHz resolution. Finally, you got all the usual play and repeat modes as seen on every other CD player under the sun, and Marantz’s tiresomely over-bright fluorescent display, which happily could be turned off. Build and finish of this Japanese-made machine were absolutely superb, needless to say.

Philips Bitstream

First, a word about the CD-15. You could say that it sounds very much ‘of its day’ – a decade before, CD players were lacking in fine detail and focus, and the the ’15 was made at a time when the goal was to wholeheartedly move on from that. So the first Bitstream Marantz flagship seems to be all about signalling its hi-fi credentials. It has a very low distortion sound, one which is extremely clear and open and explicit by the standards of the day. It’s muscular too, prompting some to say at the time that it sounded very ‘American’. What it does not do however is sound particularly ‘European’; absent is that wonderfully fluid, organic character that Philips-based machines traditionally had. One can now see why some Marantz fans yearned for something more familiar.

Philips multi-bit

The CD-15 was a great CD player, done at a time when CD was finally coming of age as a mature and credible music carrier. It was comprehensively better in so many respects than what had come before, and yet somehow it just didn’t stir the emotions or satisfy the soul. In this context, the apparently rather bizarre decision to exhume those old Philips multi-bit DAC chips for its replacement, now begins to make sense. The CD-7 sounds spookily similar to the CD-15 in a number of ways, yet profoundly different too. In makes a dramatically more musical noise – things aren’t flat and matter-of-fact, and instead the recording sounds far more animated and full of life. Listening to the CD-7 after the CD-15, it’s crystal clear that Marantz engineers achieved their stated aim of making a memorable and unique silver disc spinner.

![Philips TDA1547 Blue Star]() Philips TDA1547 Blue Star

Philips TDA1547 Blue Star

Indeed, it has a wonderful zest to how it goes about making music. It’s fast and full-on, making for a highly animated sound that makes listening consummate fun. Bass is expressive, fluid and tuneful, while its treble seems eager to make itself more than just an adornment. The midband of the CD-7 is highly percussive, and grabs the phrasing of the music by the scruff of the neck. There’s no sense that the listener is ever left to his or her own devices; this machine takes you on a musical journey whenever you push the ‘play’ button. It makes most machines of its era seem musically rather lost and aimless sounding. One key facet of this is the CD-7’s dynamic performance; it seems particularly adept at tracking the changes in the intensity of the music, as well as being very deft at reproducing musical transients.

Tonally, this classic Marantz isn’t quite as sweet and warm and you might think. We were well past the days of those early Philips-based machines, and the result is a neutral product that errs only very slightly towards the ‘sweet’. It certainly doesn’t have the ‘bright white’ sound of some rival Japanese machines of the day, but nor is it the digital equivalent of an old tube amp either! Don’t buy the CD-7 if you’re after a trip down memory lane – instead, it’s a fascinating conjunction of the old and the new, one which makes for its own unique sound.

![Philips TDA1541 S2 double crown]() Philips TDA1541 S2 double crown

Philips TDA1541 S2 double crown

A true modern classic

Marantz only made 750 CD-7s, which is one of the main reasons that they have held their value extremely well. These days, expect to pay between £1,500 and £2,000 for a mint specimen, and don’t think you’ll pick one up on your next trip to the audio jumble – they’re rare and need searching out. Find a good one though, and you’ll have an extremely special silver disc spinner that plays good old fashioned sixteen bit digital audio better than almost everything – and a true modern classic too. There was nothing quite like before, or after.

Marantz CD7

Marantz CD7

Marantz CD15

Marantz CD15

Marantz CD7 and Marantz CD15

Marantz CD7 and Marantz CD15

Philips TDA1547 Blue Star

Philips TDA1547 Blue Star

Philips TDA1541 S2 double crown

Philips TDA1541 S2 double crown